The story presented here takes place in the Dallas jail, 34 hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The facts have been called by G. Robert Blakey, Chief Counsel for the House Select Committee on Assassinations, "real," "substantiated," "very troublesome," and "deeply disturbing." He went on to say that, while this is only a small part of the large mystery of the Kennedy assassination, it raises questions that remain "unanswered," makes inferences which are "ultimately inconclusive," and is therefore an "unanswerable mystery." Here's why: If the following eyewitness testimony is accurate — and Blakey and his Congressional committee's staff have said that it is — Lee Oswald, while under arrest in the Dallas jail, attempted to place a call to a former Special Agent of U.S. Army Counterintelligence. And that alone is enough to raise serious questions about who Oswald was; with whom did he work and/or associate; did he have connections to American intelligence (as Senator Schweiker's statement above asserts); and finally, the big one, does this put us any closer to knowing if he acted alone to kill President Kennedy on November 22, 1963? Number, Please? It's Saturday night, November 23, 1963, in the Dallas jail, sometime before 10:00 p.m. Though of course he cannot know it, Lee Oswald has only 12 hours left to live. Around this time, he lets it be known that he wishes to make at least one telephone call. That request set in motion the following series of events.Between 10:15 and 10:35 p.m., 43-year-old telephone switchboard operator Alveeta Cave Treon arrived at work on the fifth floor of the Dallas Municipal Building, to begin her 11-to-7 shift. She came in well before her shift began in order to relieve one of the operators who had previously asked to leave early that night. Seated near one end of the ten-position switchboard was another operator, Louise Swinney, and Mrs. Treon took a position near the other end, leaving about four to six seats separating them. In this first section of the article, the narrative is told from the perspective of, and uses quotes from the testimony by, Mrs. Treon (1920-1999). As soon as Mrs. Treon sat down to begin work, Mrs. Swinney told her there would be two men — "I am not sure if she said Secret Service, homicide, or what" — coming to the switchboard room to listen into a call. "They had told her that they would be taking Lee Harvey Oswald to a telephone to let him make a call." Mrs. Swinney made it quite clear that their superiors had sent instructions for them to cooperate with the men. About 10 minutes later, said Mrs. Treon, "a knock came to the door, which is kept locked at night for security purposes. Mrs. Swinney, who was closest to the door, went and unlocked it. Two men identified themselves to her, I think by showing their identification cards. I didn't remember what they said but I assumed they were the expected law enforcement men. They entered the room and immediately went to the equipment room." As they were the only two operators at the board at that time, Mrs. Treon said she knew that either she or Mrs. Swinney would handle Lee Oswald's call when it came through. "A few minutes after the men went into the private room, a red light came up on the board showing a call from the jail. Mrs. Swinney and I both plugged in simultaneously to take it." Mrs. Treon was the first to say "Number, please," but it was Mrs. Swinney who took charge of the call. "[I] let her handle it alone," Mrs. Treon said later. "I did not unplug. I quit trying to handle the call and let her, but I stayed plugged in with my key open." This meant that Mrs. Treon could hear everything that was being said to Mrs. Swinney by Lee Oswald. Mrs. Treon's 20-year-old daughter, Sharon — who also worked for the Dallas Police Department, as a stenographer in the Records Office — had come in to visit with her mother that night, and was sitting in a chair a few feet away from the switchboard. Sharon asked her mother, if it worked out that she handled Lee Oswald's call, "to make a memorandum of it — a copy of the original ticket — as a souvenir." When it was clear that Mrs. Swinney was taking the call, Mrs. Treon sat back and listened. 'I Was Dumbfounded.' Mrs. Treon continued: "I heard her repeat a number to the caller and saw her write down details on a notation pad, which is normal routine. She then closed the key so no one on the line could hear her, then called the two men in the room on a line and said that Oswald was personally placing his call." "I listened and watched very carefully for Mrs. Swinney to place the call with the long distance operator. She appeared very nervous and visibly shaken. For a few minutes she just sat there trembling." Mrs. Treon would later comment that she understood Mrs. Swinney's nerves. "I continued watching and listening but she did not place the call." Because Mrs. Swinney's key was closed, it was not possible for Oswald or the men in the equipment room to know what was happening, nor whether she had placed the call that Oswald had requested. "I was dumbfounded at what happened next. Mrs. Swinney opened the key to Oswald and told him, 'I am sorry the number doesn't answer.' I am pretty certain she said number and not numbers. She then unplugged and disconnected Oswald. Immediately, then, the two men in the equipment room came out, thanked us for our cooperation and left." Mrs. Treon would later say that her "lasting impression of the events that night is that Mrs. Swinney had been instructed by someone to not put the call through to Oswald." That belief was strengthened, she said, "by the fact that Mrs. Swinney did not leave work as soon as Mrs. Treon came on that night as she usually did. Instead she remained as though she had been assigned to handle the call." In 1978, Captain Will Fritz of the Dallas Police Department was asked by a Congressional investigator if he remembered sending any of his homicide detectives to the Switchboard room to monitor Oswald's calls. Captain Fritz said he did not remember giving those orders, "but he stated that it still could have happened." He further noted that Dallas Jail records "show nothing relating to a call from Oswald to John Hurt," but that would be consistent with the fact that the call was never attempted, and Mrs. Swinney made no official record of Oswald's request. The LD Call Slip. In 1963, switchboard operators who placed Long Distance (LD) calls for people from inside the jail were required to fill out an LD ticket and turn it in for accounting purposes. However, such tickets were not required to be turned in for long distance calls that did not go through. Mrs. Treon was later asked if she knew what Mrs. Swinney did with the LD ticket she had begun to fill out, but she said she had no idea what had become of that ticket, though the normal thing would have been for her to throw it in the trash. However, because she had kept her key open when Mrs. Swinney was talking with Oswald, Mrs. Treon heard and made notes of all the information he had given concerning the call he wished to place. Surell Brady, a Senior Staff Counsel for the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), summarized Mrs. Treon's version of events this way:

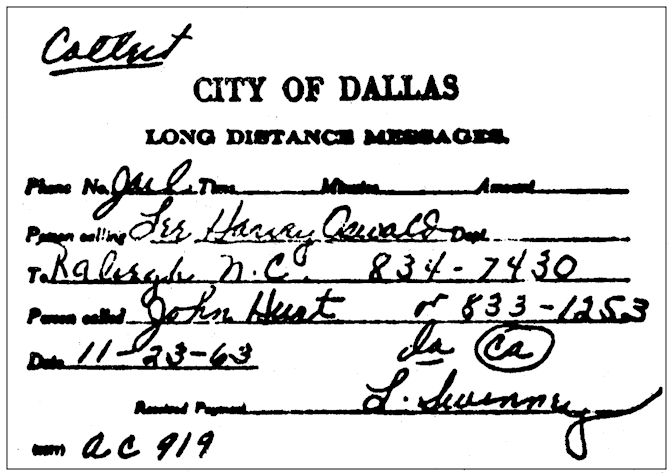

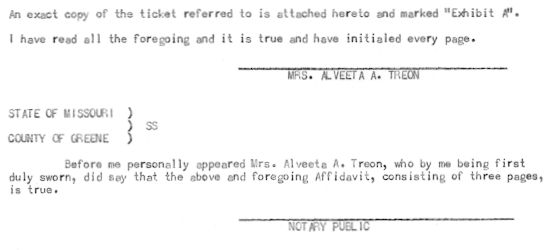

Mrs. Treon's LD call slip, which I have digitally remastered for clarity, is reproduced here:  How We Know What We Know What Mrs. Treon recorded for history on her LD slip is that Lee Oswald requested to call a "John Hurt" in Raleigh, North Carolina. But what would become important is the fact that the John Hurt who had the first phone number on the slip was a former Special Agent in U.S. Army Counterintelligence. In short, Oswald attempted to place a call from the Dallas jail to a member of the American Intelligence community on Saturday evening, November 23, 1963, but was mysteriously prevented from completing the call.Could it be that one of the most interesting and potentially important aspects of the assassination of President Kennedy may not have anything to do with the murder itself? This story of the President's accused assassin attempting to place a call to a former member of the American Intelligence community has simmered on the back burner of the investigation since its discovery. It is considered by many leading assassination authorities to be a key in the unsolved mystery — if not in being able to determine if Oswald was the lone assassin, then at least in understanding more about who he was or (perhaps more important) who he thought he was. Oswald's movements and statements inside the Dallas jail up to the time of his murder have always been a huge mystery, and any clues to what happened during that time are vigorously sought by all researchers. So when Mrs. Treon's story surfaced that Oswald attempted to place a call from the jail to a person whose name had not otherwise entered the assassination investigation, it was big news. The Sheriff and the FBI. How did we come to know Mrs. Treon's story of what she witnessed and recorded on that night in 1963 — now known as The Raleigh Call? In September of 1965, Mrs. Treon and her family, along with her souvenir LD call slip, moved from Dallas to Springfield, Missouri. And it was a "casual mention," as she described it, to a friend of hers about her experience the night of Oswald's aborted phone call that set things in motion.  Sheriff Mickey Owen When interviewed by the HSCA's Surell Brady, Smith confirmed Mrs. Treon's statement that he had contacted Sheriff Owen with the story, thinking it was something that law enforcement would be interested in. Smith knew the Sheriff through his employment at that time as a custodial officer of medical records at the Federal Penitentiary in Springfield. After hearing some of the details of Mrs. Treon's narrative, Sheriff Owen thought it credible enough that it should be turned over to the FBI. He contacted Jim Mitchell of the FBI Springfield (MO) office, and later told investigators that Mitchell interviewed Mrs. Treon and "did some type of investigation." When the FBI visited her home, Mrs. Treon said the men "appeared interested in the information as though they were hearing it for the first time," and they took with them her LD call slip in order to make a copy of it. When some time had passed and the LD slip had not been returned to her, she contacted Sheriff Owen, who was able to get it back for her. The Affidavit and Exhibit A. At some point in early 1968, someone with much (but, as it turned out, somewhat flawed) information about Mrs. Treon's testimony concerning the Raleigh Call, prepared a statement in proper affidavit form ("Mrs. Alveeta A. Treon, of lawful age, being first duly sworn, deposes and says as follows...." etc.). Attached to it was a copy of her LD call slip, marked "Exhibit A." Who would have done this, and more to the point, who would have had sufficient legal standing and knowledge to write it in correct form? Sheriff Owen immediately comes to mind, and this is bolstered by the fact that the document is written in and for Greene County, Missouri. However, Sheriff Owen told the HSCA that "he did not recall helping her prepare any kind of affidavit about the information." (Below is an excerpt of the affidavit, photocopied from the actual carbon copy made at the time the affidavit was originally typed.)  Another possibility, though perhaps less likely, is that the FBI may have prepared the affidavit after their interview with Mrs. Treon. They did, after all, take away with them her LD slip, which would become Exhibit A. But would they have prepared an affidavit headed "State of Missouri / County of Greene"? Mrs. Treon never saw this document until about 10 years after her interview with the FBI, and she certainly never signed it (therefore it was never notarized). When attorney Bernard Fensterwald first sent me a copy of the affidavit, he told me that he assumed Mrs. Treon refused to sign it on advice from her lawyer, though this does not appear to have been the case. It became clear that Mrs. Treon had not seen the contents of "her" affidavit when HSCA Special Counsel Surell Brady asked her about some of the things contained in it. Brady therefore sent Mrs. Treon a copy of the document, and asked her to respond to two sets of questions concerning it: "(1) Did you give the information in the affidavit? If so, when and to whom? Was the affidavit ever signed by you and notarized? (2) Is the information contained in the affidavit correct and accurate? If not, please indicate on the affidavit itself any inaccuracies or misstatements." As it turned out, it would be a trash can that would provide Mrs. Treon with her biggest problem with what appeared in the document. Here is how the original, unedited version of the affidavit (written as if in first person by Mrs. Treon) describes the series of events after Mrs. Swinney failed to place Oswald's call:

When all that was available to researchers was this unrevised, unedited, inaccurate copy of the affidavit (and its Exhibit A, the LD call slip), the "second hand" depiction of Mrs. Treon's going through the trash can for information about the call caused some to doubt that the call ever existed. In 1970, researcher Paul Hoch, among the first to comment on the Raleigh Call, used the trash can incident to conclude that an inebriated John David Hurt must have attempted to place a crank call into the jail to Oswald and that Mrs. Treon "picked up the wrong piece of paper — the one relating to Hurt's attempted call to Oswald — and recorded it as if it were the call from Oswald (probably to attorney Abt) which she had just witnessed." (See below for more on Hoch's theory.) Mrs. Treon, however, unequivocally stated that whoever wrote up the affidavit document got that part of it very wrong. In the corrected copy of the affidavit that she returned to the HSCA, she wrote this about what Mrs. Swinney did with the LD slip she had written out: "I did not say this. I do not know what Mrs. Swinney did with her L.D. ticket." And concerning the assertion that she relied on waste paper from a trash can for her information, she wrote this: "I did not say all this. I was asked if I knew what Mrs. Swinney did with her ticket. I said I had no idea, that tickets on L.D. calls not completed were not normally kept but I did not know what she did with it. I heard Oswald place the call — give his name etc. as I was on the line." Mrs. Treon did suggest, though, that had the FBI asked her what Mrs. Swinney did with her LD call slip, it would have been logical for her to tell them that she probably threw it away, though she does not know that for certain. Enquiring Minds, the Secret Service, and FOIA. Once the affidavit had been written, no later than early 1968, it did not take long for at least some people to come to know about it and its attached LD call slip. When Winston Smith, Mrs. Treon's friend who contacted Sheriff Owen on her behalf, was interviewed by Surell Brady of the HSCA, almost as an aside he revealed a potentially provocative and intriguing detail. He told her that, about a week after he informed Sheriff Owen of Mrs. Treon's story, a journalist "named Ian Calder or Caldwell contacted him about the information." Smith confirmed the "national" stature of the journalist who contacted him by saying "he has since seen stories by Calder in the press."  Iain Calder What makes this both relevant and intriguing is not Calder himself, or even the National Enquirer — it's the timeline and all that flows from that. Follow this closely. If Winston Smith's testimony to the HSCA is to be believed, he called his friend Mrs. Treon in mid-January 1968, telling her he had called Sheriff Owen about her knowledge of the Oswald phone call. We must ask, who knew what at this point? Mrs. Treon had confided the story to Smith, who had just called the Sheriff. Nevertheless, according to Smith, "about a week later" Iain Calder "contacted him about the information" on the Raleigh Call — indicating he was already on the story! In that week, could Sheriff Owen have had time to interview Mrs. Treon, and could the FBI have been contacted by Owen and had time enough to interview her that quickly? It seems unlikely. But nevertheless, here is Iain Calder at the Enquirer already with enough information about the story to know whom to call. Who was his source, my enquiring mind wants to know?  Bernard Fensterwald

Abraham Bolden Bolden was appointed by President Kennedy to be the first African-American presidential Secret Service agent, where he served with distinction and was once referred to by the President as "the Jackie Robinson of the Secret Service." Bolden's record with the Secret Service was particularly stellar in the fight against counterfeiting, and he was once second in the nation in successfully closing such cases. His perception of the professionalism of many Secret Service agents, however, was not at all positive. Early in 1964, he told others that he planned to testify before the Warren Commission, which was then investigating the assassination of the President, to inform them of his personal knowledge of the Service's misconduct with alcohol, drunkenness, use of official cars to transport women companions to bars, and the like. Said Bolden at the time, "I wanted to, and I still intend to, tell the commission about the laxity and nonchalant attitude of Secret Service agents handling the President." Bolden related that a Secret Service agent named Harvey Henderson, a Southern bigot, was sacked from the White House detail in October 1963. The firing of Henderson was referred to in an FBI interview summary document as "mysterious." Quite possibly referring to Henderson, Bolden was quoted as saying, "I have evidence that a member of the Secret Service had a part in the planning of the assassination. Someone, an agent, could be indicted in it." Before he could testify, however, he was arrested and indicted for soliciting a bribe from a counterfeiting ring, corruption, and conspiracy. The fact that the alleged bribe was supposed to have come from someone Bolden was investigating and trying to build a case against made the sudden bribery allegation seem very "convenient" to some in law enforcement. Bolden was convicted, still loudly proclaiming his innocence, and claiming he was being jailed to silence his attempt to tell of a plot in Chicago to kill the President three weeks before Dallas. Many researchers into the Kennedy assassination came to believe that he had been framed, not least because of his sterling reputation in law enforcement, and they began efforts to help clear his name. By December of 1967, Bolden was serving his sentence at the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. His attorney, John Hosmer, along with Warren Commission critic and author Mark Lane, and Richard Burnes, an assistant to New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, held a news conference, where they once again alleged the foiled and yet suppressed plot to kill Kennedy in Chicago. Claiming that the National Archives was hiding documents about the Chicago plot that would exonerate Bolden, two and a half years later outspoken and controversial Chicago researcher Sherman Skolnick filed a Freedom of Information (FOIA) suit (Skolnick v. National Archives and Record Service, April 6, 1970). It was this lawsuit that would tie Bolden's case, at least peripherally, to the Raleigh Call. As part of the documentation for his FOIA lawsuit, Skolnick included copies of the Treon affidavit and her LD call slip. According to Secret Service documents, Skolnick's complaint alleged that Oswald made a collect call to John David Hurt of Raleigh, NC, and that Hurt's background included service as a special agent of the United States Army Counterintelligence Corps. It is evident, then, that it did not take long for a direct link to be made from Oswald's call from jail to John David Hurt and his WWII Military Counterintelligence service. The lawsuit was ultimately fruitless, but it did have the effect of finding a common, if admittedly tenuous, thread that ran through The Raleigh Call, Mrs. Treon, Sheriff Owen, Springfield, John Hosmer, Ian Calder and the National Enquirer, Abraham Bolden, the Secret Service, and a reported Chicago plot to assassinate the President in early November 1963. The HSCA's Investigation Goes to Raleigh. Jump ahead to 1977, and the creation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). On August 4, Jim Kostman, Research Director of the Assassination Information Bureau (AIB), pulled a first-generation carbon copy of Mrs. Treon's three-page, undated, unsigned affidavit from an AIB file labelled "Treon," and sent a photocopy of it to the HCSA, indicating that he had "no knowledge of how this affidavit was obtained." Kostman described it as "an unsigned copy of a notarized affidavit," but he clearly misspoke. Obviously if a document is "unsigned," there is no signature to be notarized. No signed copy of the affidavit has ever surfaced, and Mrs. Treon herself told the HSCA that she "definitely would not have signed" a document that contained the errors she found in it. The file labelled "Treon" still exists in the AIB's files, which have become part of the mammoth Assassination Archives and Research Center collection, but it contains only the third (and least interesting and informative) page of the carbon copy of the affidavit. Where the first two pages have gone is a mystery. When the HSCA received the Treon affidavit, along with a copy of the LD call slip, Senior Staff Counsel Surell Brady was assigned to head up the investigation of the incident, and ultimately to write a report detailing the findings of that investigation. Though the HSCA's final published Report did not mention the call nor even acknowledge her work, Brady wrote a 28-page internal memorandum (Report: John Hurt Allegation ) outlining the results of her group's investigation of the incident. Her Report remained unpublished until I transcribed it in full, and placed it on my website's collection of documents concerning the Raleigh Call. That group's work began, naturally, by contacting and interviewing Mrs. Treon and, after that, her fellow operator, Mrs. Louise Swinney, who by that time had become supervisor of the Dallas City Hall Telephone Operators. When HSCA investigator Harold Rose approached 59-year-old Mrs. Swinney and identified himself, he reported she became "very nervous" and asked, "Do I have to talk about it? Are you going to harass me? What will happen to me if I don't talk about it?" After her fears were somewhat allayed, she told Rose that "sometime around 7 p.m., November 23, 1963, she was told by the DPD [Dallas Police Department] that if Oswald tried to make any phone calls, they would send two men to the telephone room to 'tap in on the line.' She stated that about 10 p.m., two DPD homicide detectives came to the telephone room and identified themselves to her." She revealed that "Oswald tried to make two calls," one to "Lawyer Apt." [sic] in New York and she doesn't remember where the other call was to." According to her statement, "she did not put either call through for Oswald." In a later interview, Mrs. Swinney was shown a photocopy of Mrs. Treon's souvenir LD call slip which shows the name "L. Swinney." She stated that it was definitely not her signature, and she was described as being "upset that someone had signed her name." (The explanation for Mrs. Swinney's name being on the LD call slip, written in the hand of Mrs. Treon, is given above.) Mrs. Swinney reiterated that she "only handled a call from Oswald to "Lawyer Apt." [sic] and another one that she cannot remember. This time, however, she added that the second call was not to John Hurt. Mrs. Swinney's references to "Lawyer Apt" are almost certainly related to Oswald's ultimately futile attempts to get in touch with New York attorney John Abt, whom Oswald wanted to represent him. Unlisted, and Yet Listed? Mrs. Treon's LD call slip is a record of an attempt to make a collect call from the jail by Lee Oswald to a John Hurt, in Raleigh, NC, area code 919, with two telephone numbers given – 834-7430 and 833-1253. What do we know about those two telephone numbers? In an insert after page 15 of her Report: John Hurt Allegation, Surell Brady incorrectly reported that the two numbers listed on the LD call slip "were unpublished in 1963." This information was supplied to Brady by Carolyn Rabon of Southern Bell Telephone Co. at 11:55 a.m. on December 13, 1978. Even if they were unlisted, Brady inquired, could Southern Bell's records supply the names of the people to whom those numbers belonged in 1963? Rabon was not sure. Fifty-five minutes later, Brady reported, Rabon called her back "to say she had had some luck getting information on the persons to whom the telephone numbers I had given her. Ms. Rabon asked me if I thought she would have any legal problems by giving me the information. I told her we would have to use the information if it pertained to our investigation. She then said she was not supposed to give out unlisted numbers, but that here she was only giving me the names, so she did not think there would be a problem." Rabon was so absolutely certain that these two numbers were unlisted in November, 1963, that she had to talk her way through an ethical quandary as to whether it was permissible to give the names of the people who had those phone numbers. She needn't have worried. A simple check of the December 1962 Southern Bell telephone directory for Raleigh, NC (which would have been current at the time of the assassination) and the December, 1963 directory (which would contain any new information and reflect any changes of listing status) shows that both numbers were published and therefore not "unlisted." Thus, both of these numbers would have been available to anyone calling "Information" in Raleigh, asking for a John Hurt. This shows the way the listings appear for those two phone numbers in two years' directories prior to and two years' directories after the assassination: From the November, 1961 Raleigh, N.C. telephone directory: Hurt John D 15 New Bern Av ................ TE4-7430 Hurt John W 315 N Boundry ................. TE3-1253 From the December, 1962 Raleigh, N.C. telephone directory: From the December, 1963 Raleigh, N.C. telephone directory: From the December, 1964 Raleigh, N.C. telephone directory: Why Southern Bell would have provided incorrect information, or how they could have made such a gross mistake, is unknown.

Who Was John Hurt? Obviously, the identity of any person whom Lee Oswald might have attempted to contact after having been arrested for the murder of the President would be of immense interest. As noted above, Mrs. Treon's LD call slip lists both of the numbers she said Oswald gave for a "John Hurt" in Raleigh, NC. In the section above, I have shown that both numbers belonged to men named John Hurt in Raleigh, and it is the first number which has received the lion's share of attention. Pat Stith  John David Hurt Hurt denied to me that he made or received a call to or from the Dallas jail or Lee Oswald. When I asked if he knew of any reason why Oswald would wish to call him, he said, "I do not. I never heard of the man before President Kennedy's death." Mr. Hurt professed to having been a "great Kennedyphile," and said he "would have been more inclined to kill" Oswald than anything else. Asked if he had any explanation as to why his name and telephone number should turn up this way, he said, "None whatever." I also asked him if he had any knowledge of the second phone number on the slip, and he said he had never had that number in his use. "My number has been the same for, oh, I'd say forty years." (Perhaps Hurt intended to say "twenty years," as both he and his wife had told HSCA investigators two years earlier. See below.) Further excerpts of my interview with Hurt can be found attached to the end of this article. The HSCA Hurt Interview. On April 11, 1978, three HSCA staff members interviewed John David Hurt in the rooming house where he lived, at 201 Hillsborough Street in Raleigh, NC. They found it important to describe the scene in some detail, noting that, at 6:00 p.m. when they arrived, Hurt's wife

Billie Greer Hurt and John David Hurt When shown a copy of Mrs. Treon's LD call slip, he identified the first telephone number as his, but said that he did not know to whom the other number belonged. Both Hurt and his wife stated that they had had their phone number "for about 20 years." He said he could not offer any explanation concerning how or why his phone number appeared on the LD slip. Additional questioning attempting to find any other possible cause for Hurt's phone number being on the LD slip produced nothing. (Above is an early photo of Billie and John David Hurt. They were married in 1939. ) Hurt told the HSCA investigators that he held a law degree from the University of Virginia, "but never practiced." After his military service, he said, he "entered the insurance business, working in claims" — first for about a year in South Carolina, and thereafter in North Carolina. He told the investigators that he was, at the time of the interview, unemployed and was "receiving full government disability." When asked how long he had been disabled, Hurt said "since 1961," but his wife stated that "it was 1955 when he became disabled." The three HSCA investigators asked Hurt about the most intriguing part of his resume, his military history during World War II. He replied that during World War II (approximately 1942-1945) he was in the Army, serving in the Army Counterintelligence Corps (C.I.C.) both in Europe and Japan. He attained the rank of Staff Sergeant.

Government Records: VA. Chief Counsel Blakey did on May 4, however, write to David Pogoloff, the Chief of the Veterans' Administration Congressional Liaison Service, asking for access to all of their "files and index references" concerning John David Hurt. It was not until September 27 that HSCA's Surell Brady was able to review Hurt's VA file. Her summary of it contained this information:

l. to r.: Ruby, Diantha, and John Hurt Hurt was small of stature, measuring only 5-foot 4-inches tall and weighing 140 pounds in 1954. He married Billie Lee Greer (1918-2000) in 1939. Hurt died December 3, 1981 in Raleigh, NC. Hurt had a troubled employment life after the War, either caused by or contributing to the steady decline in his physical and mental health. According to a bio statement prepared for attorney Bernard Fensterwald (see below), "Hurt was appointed Accident Evaluator in the N.C. State Motor Vehicles Department on January 11, 1954 at a salary of $3,936.00 per year. A former co-worker advised that he was highly efficient in his work and well liked until April 1955 when he was suspected (later proven) to have been favoring a particular adjustment firm. He admitted the charge but denied any kick-backs and was allowed to resign on May 2, 1955. His file was noted, 'not recommended for re-employment due to conduct not becoming to a State official.'" The bio summary continues about his mental health: "Dr. R.L. Rollins Jr. of a State hospital in Durham advised the S.B.I. in confidence that the subject is manic-depressive-paranoid, very dangerous to society, and capable and likely to carry out threats of death or violence. Under no circumstances should any threats he makes be taken lightly. Hurt has made threats in recent weeks which have come to the attention of the S.B.I. [NC State Bureau of Investigation]. He is Secretary of the 17th Precinct Democratic Club in Raleigh and has written critical and scathing letters to the Governor of North Carolina arising from the Governor's failure to visit the 17th Precinct Club. When a Governor's Aide went to see him to placate his ire Hurt was very critical and denunciatory and followed with more vitriolic letters about the Governor and the Aide. Another Aide was then sent to see him and was told to 'get out or I'll give you both barrels of a double-barrelled shotgun.'" John David Hurt was known to some assassination investigators as early as 1968, the year of Mrs. Treon's affidavit. The same investigator who prepared a three-page biographical outline of Hurt also wrote a letter outlining the results of a call he made to Hurt that year, pretending to be an old comrade of his, Edgar Eugene Bradley. Attorney Bernard "Bud" Fensterwald, Chief Counsel of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure, for whom these documents were prepared, sent me both the letter and the biographical materials. The conversation in the fake phone call turned to the subject of the Kennedys: "Hurt went on to tell me all about his arrest in Raleigh while driving on a one-way street with an opened bottle of Jack Daniels Green Label.... He invited me to stay with him and the 'old lady' and said they were still drinking and fighting together. He said that 'those Kennedy boys always got him in trouble.' It was when John got killed that he got in jail in Louisiana and when Bobby got killed he was jailed in Raleigh." Incoming or Outgoing? So did Oswald attempt to make a call to Hurt from inside the jail? If so, why was his call thwarted by men in authority? And why would Oswald want to call a man in Raleigh, North Carolina, who seems never to have heard of him before — especially when you consider the man was formerly Military Counterintelligence, but one who had developed terribly difficult personal, medical, physical, and mental problems? And if Oswald didn't call out, and the only Hurt connection was an incoming crank call, how do we explain Mrs. Treon's statement, one she gave reluctantly and with no attempt to gain publicity?To begin with, let there be no doubt — Surell Brady and her investigative team for the HSCA believed in the legitimacy of Mrs. Treon's story, and therefore of the Raleigh Call. The section titled "Conclusion" in her Report makes it clear: "The information provided by Mrs. Treon, her daughter, and Louise Swinney all indicate that Oswald did in fact attempt to place a call from the Dallas City Hall Jail on the night of November 23, 1963." The Report further states that, while it could not find corroborative evidence that Lee Oswald attempted to call John David Hurt (nor, it might be added, did they find evidence to the contrary), they "found no evidence that Mrs. Treon had any motive to invent the story, especially with such precise details as the actual phone number listed to John Hurt." What the Hurts Said. When interviewed by Surell Brady and members of her investigating staff, both John David Hurt and his wife Billie Hurt adamantly told them the exact same thing they would tell me two years later (see above) — that he had made no calls to the Dallas jail, and that he had received no calls from Oswald. The latter of these two is confirmed by Mrs. Treon's testimony. John Hurt died a year after I interviewed him, and one researcher has written that, a year or so after Hurt's death, he got Billie Hurt to finally admit "the truth" about the Raleigh Call. Here is how author James W. Douglass presented and critiqued that finding in his book JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters" :

Raleigh attorney Paul Creech, who worked with Billie Hurt in settling her husband's estate (and later settling Billie's), recently wrote of his own dismay at not inquiring further about the Raleigh Call, and revealed Billie Hurt's state of mind about it:

Other Theories and Explanations. Surell Brady's Report goes on to explore a few alternative theories to see if they meet the test of the known evidence, and perhaps it would be good to do that here, as well. Let's first explore the possibility that Oswald did not make the call. Anthony Summers, in whose 1980 book Conspiracy the Raleigh call surfaced immediately after the HSCA closed up shop, told me privately that some researchers believe the call in question to have been incoming to the jail, not an attempt by Oswald to call out. One well known assassination researcher, Paul Hoch, explained to me an alternative theory of his concerning the events of November 23. Hoch believes that Hurt, or someone using his name and telephone number, called the Dallas jail prior to 10:15 p.m. on that date, requesting to speak to Oswald. He theorizes that whoever took the call, possibly Mrs. Swinney, scribbled down some information, decided it was a crank call, and threw away the slip. Later, when Oswald made the call that Mrs. Treon overheard, Hoch says it was to the New York attorney John Abt, whom Oswald wanted to represent him. We know from testimony from a Secret Service inspector named Kelley that Oswald expressed interest in getting help in reaching Abt by telephone. He then suggests that what Mrs. Treon mistakenly pulled from the trash can was information on the earlier crank call from Hurt. There are three problems with Hoch's explanation of events, however.

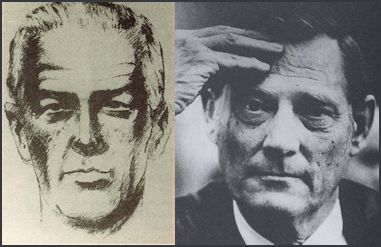

Anthony Summers and G. Robert Blakey Blakey confessed to being troubled by the call as well, but, to Summers' surprise, for the exact opposite reason. As a subsequent interview I had with Blakey confirmed, "The call apparently is real and it goes out. It does not come in. That's the sum and substance of it." Blakey continued, "It was an outgoing call, and therefore I consider it very troublesome material. The direction in which it went was deeply disturbing." It should be noted that one reason for Summers' surprise at Blakey's strong and unwavering confirmation of the importance and direction (outgoing, not incoming) of the Raleigh call was the fact that it came from Blakey himself. If the legitimacy of the Raleigh Call points us in any direction at all concerning who might have been involved in a conspiracy to kill the president, it would tend to make us look in the direction of the American Intelligence community. After all, there is no doubt that John David Hurt was a Special Agent in Military Counterintelligence during WWII. However, Blakey was well known for his belief that the conspiracy to kill Kennedy came from Organized Crime (just look at the title of one of his books: The Plot to Kill the President: Organized Crime Assassinated JFK ). He was often quite hostile about any theories that might look elsewhere for culprits, such as U.S. intelligence operatives. No doubt Summers considered that Blakey must be extremely convinced of the Raleigh Call for him to support it in the face of what it might imply about his "only the Mafia did it" belief. Chicago researcher Sherman Skolnick, whose FOIA lawsuit against the National Archives was referenced above, agrees with Blakey and believes the call was definitely outgoing. It was Skolnick's theory that John Hurt "was Oswald's ticket to verify that he [Oswald] was a lower-level intelligence operative." (More on that as a possibility in the next section.) One fact uncovered by Skolnick in sworn statements for his lawsuit, which were not heard in open court, is that the Secret Service took a sudden interest in someone named Hurt on November 23, 1963. In a statement from former agent Abraham Bolden, who was duty officer for the Secret Service's Chicago office that weekend, he claims that the Dallas Secret Service office called him late on the 23rd and asked for a rundown on any phonetic spelling of "Hurt" or "Heard." Obviously, something happened in Dallas that day to cause such a far-flung investigation all the way to Chicago. Whether this was because of Oswald's interest in a party named "Hurt" or or some other lead that had come into authorities is still being debated. So... Incoming or Outgoing?? What is the preponderance of truth here? While we cannot 100% rule out the possibility that, "in a drunken stupor," John Hurt made a crank call into the Dallas jail, trying to speak to Lee Oswald, the facts and testimony as we know them now do not point in that direction. The narrative in Mrs. Treon's corrected affidavit simply will not allow for the call in question to have been (or to be confused with) a crank call from outside the jail. It therefore comes down to an issue of Mrs. Treon's credibility as an ear- and eye-witness. There are three major, incontestable facts about Mrs. Treon and her actions in relation to the Raleigh Call: (1) She immediately recorded what she heard Lee Oswald say onto the LD slip; (2) She kept the actual LD slip carefully in the upcoming years; and (3) She did not seek fame or monetary gain in exchange for telling her story. When you add to that the fact that nothing major, substantive, or proven has come forward in the time since her affidavit was made public which contradicts her story, then she emerges as extremely credible and her story probably true. Therefore, we can credibly say that the evidence points to the fact that Oswald attempted to call a "John Hurt" in Raleigh, North Carolina, from the Dallas jail, for reasons still unknown.  Sen. Richard Schweiker Those questions lead back to the opening quote from Senator Richard Schweiker, who in the mid-1970s chaired a Senate subcommittee charged with investigating the role of U.S. Intelligence (specifically the CIA) at the time of the Kennedy assassination. Schweiker came to thoroughly distrust the conclusions of the Warren Commission, the Presidential panel chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren and tasked by newly sworn in President Lyndon Johnson with reporting the truth to the American people about who killed JFK. Said Schweiker, "I think the Warren Commission is like a house of cards. It's going to collapse." After months of intensive study and research, Schweiker without hesitation asserted on the CBS News program Face the Nation in 1976: "We don't know what happened, but we do know Oswald had intelligence connections. Everywhere you look with him, there are the fingerprints of intelligence." The Fingerprints of Intelligence In my writings and lectures over the last 40 years, I have developed and asserted two major propositions about Lee Oswald. First, if you believe it even possible that Oswald was involved in a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy, then the best way to find out who might have been involved in that conspiracy is to examine the type of people with whom Oswald associated in the months and years prior to Dallas. And second (which derives from the first, and is a corollary to Schweiker's "fingerprints" metaphor), it seems almost certain that either Oswald was working for American Intelligence (no strong proof of this), or was being made to think he was (far more likely, it seems to me). The aspects of Oswald's life and associations which make the above seem likely are far to numerous and complex to be within the scope of this article.How does this relate to the Raleigh Call? Sherman Skolnick's theory (see above) was that John Hurt "was Oswald's ticket to verify that he [Oswald] was a lower-level intelligence operative." In other words, Skolnick was saying that Oswald was in fact a bona fide "lower-level intelligence operative," and that he had been given John Hurt's name and location, and told that if he ever got into trouble from which he was unable to extricate himself, he should not call those with whom he was working but instead call Hurt. Hurt would then contact the Intelligence higher-ups, and they would come to Oswald's rescue. Let's examine how this fits inside classic spycraft procedure.  R.B. "Bernie" Reeves  Victor Marchetti This brings us back to the proposition I referred to earlier: that Oswald's life, his connections, the people he surrounded himself with, and his actions prior to Dallas strongly suggest that either Oswald was working for American Intelligence, or was being made to think he was. Both of these would put the "fingerprints of intelligence" on Oswald that Sen. Schweiker so plainly saw, therefore both need to be considered, if we accept Marchetti's "cut-out" explanation. Let's first examine a scenario in which Oswald was actually, knowingly working for American Intelligence. In that case, Marchetti said it is a safe assumption that he would have been supplied a cut-out, a "clean" emergency contact. Was it John David Hurt? With his experience in Military Counterintelligence in WWII, Hurt seems at first glance a likely candidate, but his failing professional, personal, medical, and mental conditions in the years leading up to the assassination seem to suggest he would have been an unreliable choice, at the very least. In the scenario in which Oswald was merely led to believe he was working as a part of U.S. Intelligence (told that he was a NOC, perhaps?), the deficits that would have made Hurt unacceptable as a real cut-out perhaps would have made him a perfect "fake" one. If someone were trying to make Oswald believe he was doing spy work, they might find someone who had the veneer of legitimacy (for example, wartime counterintelligence experience), but who had hit such hard times that, were it to become known, no one would believe he could possibly be involved in any way. Oswald would think it was legitimate right up until the time he either called the man and found out it was a dead end, or attempted the call but was thwarted by men in suits. While there is no proof of any of this, it seems to fit the facts as well as anything else. If we cannot know who, Marchetti told us, we can at least understand why. Whether guilty or not of the assassination, once inside the Dallas jail Oswald was looking for some way to assure his interrogators, which may well have included agents of the CIA (according to Marchetti), that he was "okay." If this were true, then much can be explained if we suggest that Oswald had been given the name "John Hurt" in Raleigh, North Carolina to call in extreme situations. If Oswald dialed "Information" (we now call it Directory Assistance) to get a phone number for that person, he would have been told there were two John Hurts listed. He would have been asked which one he wanted, and Oswald would most likely have said "both." Since we now know (no thanks to Southern Bell Telephone Company; see above) that telephone numbers for two John Hurts in Raleigh were listed in November, 1963, Oswald could have memorized both numbers. That would explain all of the information Mrs. Treon said she heard Oswald give when he asked to make the call, and which she then wrote on her souvenir LD call slip — the name John Hurt, Raleigh, NC, the area code 919, and the two phone numbers. That the call was blocked from being placed, presumably by the "agents" in suits in the next room, just adds another disturbing, and as yet unsolved, aspect to the case. ONI/Nags Head and Maurice Bishop of the CIA. As indicated above, it is beyond the scope of this article to detail all of the aspects of Lee Oswald's life prior to, and immediately after, the assassination which point toward his having acted as if he were involved in some Intelligence operation(s). However, Marchetti did put Reeves and me onto one suggestion he had that might explain why Oswald's "handlers" would have chosen a "cut-out" for him in North Carolina.  Lee Oswald in the Dallas jail. This process is known as "doubling," explained Marchetti, as the young men would then in effect be double agents for both American and Soviet intelligence. Once placing an agent in the KGB, American intelligence could then begin funneling in disinformation. According to Marchetti, this was the plan for Oswald, and he strongly hinted that Oswald would have passed through ONI Nags Head on his way to defect to the Soviet Union. Further excerpts of our interview with Marchetti can be found attached to the end of this article. There exists in the literature some corroboration of Oswald's participation in such a project, and the existence of the ONI base in Nags Head, NC. Here are a couple of representative examples. Attorney, author, and assassination researcher Mark Lane in 1978 interviewed David Bucknell, described as "a former Marine who had served with Oswald in Santa Ana, California." Lane wrote about Bucknell's recollections of several clandestine operations that Oswald had been involved in, culminating with a meeting that mapped out Oswald's future for the following two years. Oswald returned from that meeting and "confided to Bucknell that he, Oswald was to be discharged from the Marine Corps very soon and that he would surface in the Soviet Union. Oswald told Bucknell that he was being sent there on assignment by American intelligence and that he would return to the United States in 1961 as a hero." Did this assignment involve a stopover for training in Nags Head, as Marchetti has asserted? At least one former CIA employee confirms oswald's presence at Nags Head. Former CIA pilot "Tosh" Plumlee testified in 2004 as follows: "When I later learned that Oswald had been arrested as the lone assassin, I remembered having met him on a number of previous occasions which were connected with intelligence training matters, first at Illusionary Warfare Training in Nagshead [sic], North Carolina." The final question must surely be, is there evidence of Lee Oswald's involvement with American Intelligence in the time immediately before the assassination? Actually, there is brand new confirmation linking a high-ranking CIA official with Oswald and the Kennedy Assassination. Space in this article does not permit a full account of the journey that ultimately led to this revelation, but it is thoroughly and spellbindingly laid out in Gaeton Fonzi's book The Last Investigation. Fonzi was an investigator for Schweiker's Senate probe into the CIA and the assassination, and later for the HSCA.  "Maurice Bishop" and David Atlee Phillips Fonzi came to know and trust Veciana's credibility, with the exception of this one thing. In his book, Fonzi recounts one of his last interviews with Veciana about Maurice Bishop: "'You know that I believe what you have told me,' I went on. 'I believe you about everything. Except when you told me that David Phillips is not Maurice Bishop.'" Right up until his death in 2012, Fonzi was certain that Veciana knew Phillips was Bishop, and that therefore Oswald had been seen meeting with a CIA official two months before the assassination. It was only after Fonzi's death in 2012 that his widow Dr. Marie Fonzi pursued Veciana, convinced him that enough time had passed, and that for the truth's sake (and to honor the work of her husband), he needed to come forward with the truth. Finally, on the day of the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination, Veciana gave her what she and Gaeton had wanted — absolute verification:

The declaration in this letter made it official — Lee Oswald had been positively identified as meeting with a CIA official barely two months before the assassination. But it was only a letter. Marie Fonzi convinced Veciana to attend the 2014 National Conference on the 50th Anniversary of the Publication of the Warren Commission Report. And so, on September 26, just outside Washington, DC, a frail 86-year-old Antonio Veciana mounted the dais and sat stoically as his son read his prepared statement to the world. It began with a single sentence that sent shivers throughout the crowded, standing-room-only great hall:

The declaration in this letter made it official — Lee Oswald had been positively identified as meeting with a CIA official barely two months before the assassination. But it was only a letter. Marie Fonzi convinced Veciana to attend the 2014 National Conference on the 50th Anniversary of the Publication of the Warren Commission Report. And so, on September 26, just outside Washington, DC, a frail 86-year-old Antonio Veciana mounted the dais and sat stoically as his son read his prepared statement to the world. It began with a single sentence that sent shivers throughout the crowded, standing-room-only great hall:

I want to unequivocally state that Maurice Bishop was David Atlee Phillips. I was literally on the front row for this history-making event, and I will have Veciana's complete assertions about his knowledge of CIA complicity with Oswald and the Kennedy assassination in an upcoming article. Conclusion It was never my intent to solve all the issues and answer all the questions about the Raleigh Call in this one article. I knew, of course, it would be impossible to do so. But my goal was to lay out in one place all that is known to this date (51 years to the day after the Raleigh Call itself) about this most intriguing incident.So where does this lead us? I've drawn some conclusions along the way here, for example, my strong belief in Mrs. Treon's veracity. This leads me straight to the conclusion that Lee Oswald did, in fact, attempt to call attorney John Abt earlier in the evening and to call a "John Hurt" between about 10:15 and 11:00 p.m. The detailed facts of the life of John David Hurt are here for the reader to draw conclusions as warranted. The same goes for Nags Head and Maurice Bishop. In the end, as I earlier surmised, it gets back to the question of whether we can know if Oswald was working for American Intelligence, or was being led by others to make him think he was — or some other explanation that takes in the dark shadows of his life prior to Dallas. One final and key thing that speaks to the importance of the Raleigh Call ultimately is that both Victor Marchetti, who is convinced of at least a partial involvement in the assassination by intelligence agents, and Robert Blakey, who eschews that explanation as unnecessary and says it was totally a Mafia plot, agree that the Raleigh Call is an important, disturbing, and factual aspect of the JFK case. Said Blakey, "I consider it unanswered, and I consider the direction in which it went substantiated and disturbing, but ultimately inconclusive." When I asked him if he would recommend that the Justice Department look into the incident, if and when it re-opens the case, Blakey said no. His reason? "The bottom line is, it's an unanswerable mystery."

INTERVIEWS

Excerpts of Interview with John David Hurt

Excerpts of Interview With Victor Marchetti

|

|

| PAGES & SITES OF INTEREST TO VISIT | |

| THESE ARE NOT PAID ADS. WE JUST SUGGEST YOU WILL LIKE THE SITES. | |

|

RETURN TO TOP |

| All content ©1995-2022. All rights reserved. |