| PHOTO GALLERY

| THE WAR YEARS

| EMAIL GROVER JR. |

THE WAR YEARS

This uncommon valor of which we speak truly flowed from everyday men and women, cast into unimaginable situations, called on to do the impossible and to conquer the insurmountable — which, selflessly, they did simply because they knew that it all depended on them and that it must be done.

|

|

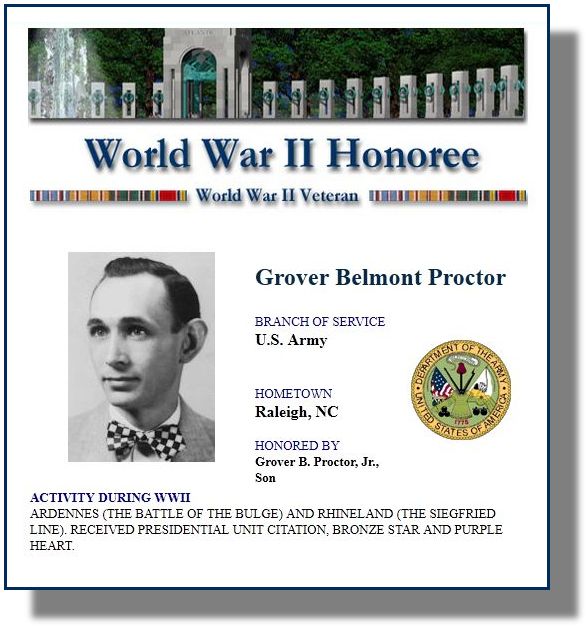

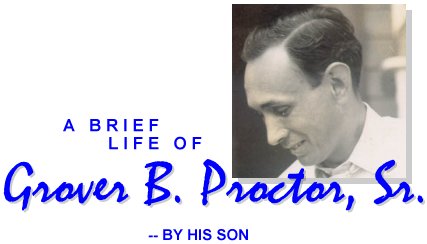

Pfc Grover B. Proctor

Army Serial No. 34 967 789

Co. "F" (2nd Battalion), 345th Regiment

of the 87th Infantry ("Golden Acorn") Division

ETO 1944-1945 |

| [Shown: Golden Acorn patch from Pfc Proctor's uniform] |

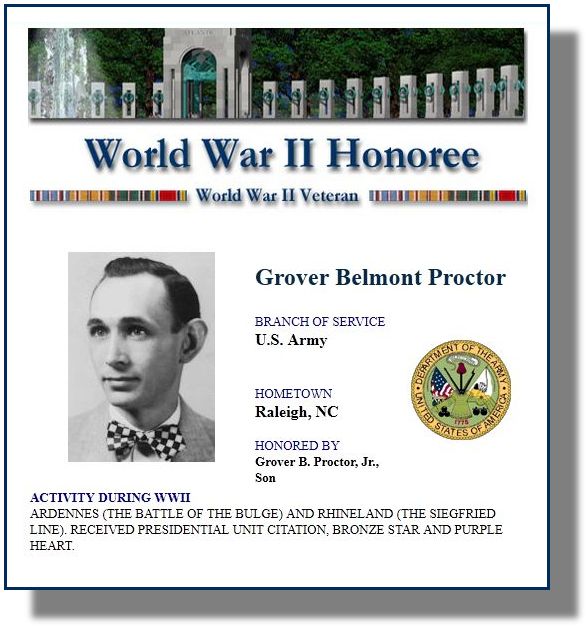

Grover Belmont Proctor was born on January 7, 1918 in Upper Town Creek Township (near Rocky Mount) in Edgecombe County, North Carolina. He married Edna Ruth Hooks of Apex, N.C., on July 11, 1943, and, at the time of his entry into the Army, he gave as his address P.O. Box 111, Apex, N.C. He was an employee of the railroad, and the Army listed his civilian occupation and reference number as "Clerk, General (1-05-010)" with the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. The report from his Army induction physical examination gives some description of him at this time. He is listed as a "white, married, U.S. citizen," with one dependent, 5'5" tall, 115 pounds, with gray eyes and black hair. It lists his complexion as "ruddy," his eyesight as 20/20 in both eyes, and he is described as having a "light frame" and "fair posture."

Grover Belmont Proctor was born on January 7, 1918 in Upper Town Creek Township (near Rocky Mount) in Edgecombe County, North Carolina. He married Edna Ruth Hooks of Apex, N.C., on July 11, 1943, and, at the time of his entry into the Army, he gave as his address P.O. Box 111, Apex, N.C. He was an employee of the railroad, and the Army listed his civilian occupation and reference number as "Clerk, General (1-05-010)" with the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. The report from his Army induction physical examination gives some description of him at this time. He is listed as a "white, married, U.S. citizen," with one dependent, 5'5" tall, 115 pounds, with gray eyes and black hair. It lists his complexion as "ruddy," his eyesight as 20/20 in both eyes, and he is described as having a "light frame" and "fair posture."

He was registered with Selective Service at the Chatham City, N.C. Local Board No. 1. He was 26 years old when he was called up into the service, and his wife remembers putting him on the bus ("I've never been more proud of him than I was that day," she would say decades later) to Ft. Bragg, N.C., on April Fool's Day, 1944. His induction date is listed as April 3 at Ft. Bragg, though it is unclear how long his basic training lasted or where it was done. He attended Clerk School at Fort Riley, Kansas, for 10 weeks in the summer, where, according to a Veterans Administration form dated December 19, 1945, he was hospitalized with pneumonia in July. (The striking photo of him, above right, was taken at Fort Riley.) His military occupational specialty and number were "Rifleman (745)" and his military qualification was listed as "SS Rifle M-1." During his time before being shipped off to the European front, Proctor was assigned to "A" Company of the 140th Regiment, 35th Infantry Division. The highest rank he held was Pfc (Private, first class).

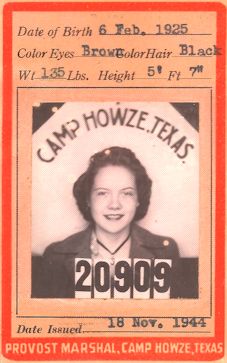

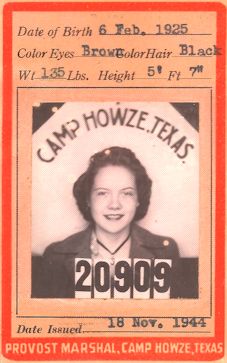

Joining the 87th. In the last months of 1944, it was clear that Proctor was headed for overseas duty. By November, he had been transferred to Camp Howze, just north of Gainesville, Texas, which was one of the largest of several infantry replacement training centers the Army constructed to accommodate the large number of new soldiers needed for deployment in Europe and the Pacific. Proctor's 19-year-old wife Ruth was able to join him there, and her photo ID (which was required to access the Camp and its facilities such as the PX) is shown above left. The snapshot of Pfc. Proctor (above right) was almost certainly taken by Ruth at Camp Howze. (I can't think of anyone else who could persuade my father to break a posted Army rule, and grin while doing it, just for a fun picture!) On Armistice Day — just a month before he shipped out — she gave him a metal-covered New Testament to take with him. On the inside cover, she wrote this from John 14:

|

Proctor left the States on December 12, 1944, and arrived in the ETO (European Theater of Operations) on December 20, where he would participate in the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge) and Rhineland (Siegfried Line) campaigns. It is unclear exactly where he disembarked, but he joined with the 87th Division in northern France at about the time they were being relieved from the Saar Valley offensive. They had sustained very heavy casualties during that incursion, and in the last ten days of December they were brought back close to full operational strength. Williams (1958) noted that between December 20 and 26, the 87th Division was attached to the Seventh Army area, XV Corps "while reliefs were in progress" (p. 363) and while a large number of replacement troops were assigned to them.

The plight of these replacements (such as Proctor) has been much commented on. Sydney Kessler, of the 347th Regiment, wrote later about his perceptions of them: "I shipped out in a unit and not as a replacement. As a replacement, it was said, your chances of survival were greatly reduced. I didn't believe this until I was in the hairy horror of full combat myself. I found myself doing what almost everyone else did. Any replacement that came into the platoon was, more or less, shunned. I just could not bear to get to know one more soldier who might get killed. I tried not to ask their names. I could not even bring myself to ask what state they came from. If they were killed, well, they were just another stranger out there" (Strang, 1999).

By contrast, James Bain, who served with Proctor in F Company of the 345th, noted that those who joined at the time Proctor did were joining a Company that had already been cemented by harsh battle conditions. "The 'original' survivors had become extremely close by that time and were 'veterans.' That explains the reluctance to quickly accept replacements as buddies!" He was equally adamant, however, that "after we attacked the southern shoulder of the Bulge (Dec. 29)" each replacement had, himself, "gone through hell and had been accepted by the men" of the squad. "He had friends!" (Bain, 1999)

Though it is unclear exactly when Proctor became attached to the 87th, it seems likely that he was assigned to the Division between December 20 and 24, as a handwritten list of the personnel of the 2nd Rifle Platoon (including Proctor's name) made by Lt. William T. Prather has survived (Prather, 1999). Lt. Prather made the list in Dieuze, France, and Regimental records show the 345th leaving the Saar Valley, moving through Dieuze on December 24. Proctor was assigned to the 2nd Platoon of F Company, 2nd Battalion, 345th Regiment, of the 87th Division, and though it is naturally the exploits and hardships and valor of these groups which will be recounted here, that is in no way to diminish the heroic efforts of all men and women who assisted in the Allied effort.

In route to their new bivouac, the 345th's history poignantly notes that the Second Battalion participated in a Midnight Christmas service in the village church of the small French town of Cutting (345th Regiment, ca.1946). By December 26 they took up a reserve position in the fields between Epoye and Biane near the cathedral city of Reims, and the Unit's Historian, 2nd Lt. Gilbert Procter, Jr. (he is no relation, but his contemporaneous history will be cited several times in this narrative) noted that "for the next three days the men had a comparatively restful time. Reims was only about 15 kilometers to the west. The men were trucked in and given showers and clean underwear and socks" (Procter, 11 January 1945, p.6). It would be the last peaceful time for Proctor before being cast into the crimson cauldron of war, until he met his bullet in Germany.

Ardennes (The Battle of the Bulge). On December 28, orders came through attaching the 87th Division to General Patton's Third Army, which was preparing to mount a counteroffensive to resist and repel the German incursion into eastern Belgium (the famous "bulge"). By December 29, the entire 345th Regiment was on the march northeast towards and into Belgium. Proctor's F Company bivouacked in the Luchy Forest at Ochamps just south of the town of Seviscourt until late on December 30, when they moved to the outskirts of Rondu to be ready for an early morning attack on the 31st, but as it turned out, the enemy had pulled back from the town. F Company led an attack to keep the Germans in retreat, but as they approached Remange, they were hit by heavy mortar fire, so they veered west of the city "only to have artillery drop in the woods to their front" (345th Regiment, ca.1946). By 1700 (5:00 p.m.), however, they had "moved through Remange, cleared it of snipers and took the high ground to the north", in the vicinity of Chapelle de Lorette (87th Division, p. 69). "Enemy tanks and infantry coming out of the Bois la Chenaie Woods continued to attack their positions on the hill" until late evening, when a burst of artillery forced the Germans to retreat into the woods (345th Regiment, ca.1946, p.17).

The 2nd Battalion (which included Proctor and F Company) stayed in positions around Rondu until January 2, when they were ordered out. On the 3rd, they moved farther east and relieved the 346th Regiment, and by January 6 F Company had taken up positions on high ground overlooking the city of St. Hubert, where their mission was to contain the city and "harass the enemy" (Procter, 6 February 1945, p.18). It was here, participating in raids on enemy positions, that Proctor spent his 27th birthday, on January 7.

The 2nd Battalion was relieved by the 347th Infantry by January 9, so that they could provide support for the 3rd Battalion, which was fighting a fierce battle for Tillet, a key Nazi stronghold. Snow was waist deep and the woods were both dark and thick in the Tillet Forest, making fighting extremely difficult. One message received at headquarters from a Lt. Colonel said simply, "Can't see 20 feet and snow hip deep" (Procter, 6 February 1945, p.5)

Tillet was finally captured on the 10th, and the 2nd Battalion was ordered to assume control of the city and establish defensive positions there. F Company was "moved into billets in Gerimont in order to give the men as much rest as possible, with special attention to their feet" (Procter, 6 February 1945, p.6). Cold, especially frostbite, was among the worst and most persistent enemies soldiers had in Belgium during the winter of 1945. William W. Fee, who was attached to the 11th Armored Division, wrote this in his diaries about living and sleeping in foxholes which the soldiers had to dig for themselves, often in frozen and snow-covered ground:

About 2300 [11:00 p.m.] we got C rations, the meat part again frozen, so we ate the bread. There was no formal guard set-up, so we tried to sleep. But even in my overcoat it was too cold. I'd dig for a few minutes to get warm, then doze for a few. My gloves were so muddy and gooey that I took them off and tried to sleep with my hands in my pockets. I wore the crude mittens that I'd made from a blanket and forgot about the gloves, which froze. To thaw them, I had to stick my freezing fingers in them and work them for hours.

Everything was frozen. I carried my canteen, a C ration meat can, and the .45 pistol under my overcoat or field jacket. Our entrenching shovel, which was made to fold up when not in use, froze in whatever position one had left it. I found that breathing on it would thaw the frozen parts.... I was told that the temperature was 8 below zero. (Fee, 1945, p.32)

|

By January 11 word began to filter in that the German "bulge" was collapsing, and patrols sent out by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions on the 12th confirmed the Nazi retreat. In an effort to press the enemy back toward its border, on January 13 the 2nd Battalion led the 345th Regiment's advance out of Tillet -- clearing landmines as they went -- northeast to Chisogne, north to Menil, through Fosset and Orreuy, on to Sprimont, and by the 14th they occupied Roumont.

It was on January 15 that orders came for the 345th Regiment to move south into Luxembourg to relieve the 4th Division. Record-breaking bad winter weather that had begun as early as Christmas now began to take a serious toll on the troops. Snow and ice covered the roads, and the temperatures dropped to consistently below freezing. The 345th took up positions along the Sauer River (Proctor and the 2nd Battalion were in regimental reserve at Consdorf), near the deserted town of Echternach, the place General Patton had called "the shoulder of the bulge" (87th Division, p. 74).

The 345th's mission was entirely defensive in Luxenbourg, holding a front 10,500 yards long, but this did not keep it immune from periodic enemy artillery and mortar shelling. The weather continued to be miserable, with sleet, snow and below freezing temperatures the norm. "On the 19th the Division put out a pass policy which permitted men and officers passes to Paris and Luxembourg. Quite a few men were able to take advantage of this. It meant a lot to the men -- a hot shower and a chance to relax and do a little sight-seeing. The city of Luxembourg was in good condition. It had received very little bombing and shelling" (Procter, 6 February 1945, p.8). There is no record as to whether Proctor was among those able to use these passes, and by the 24th, all such passes were cancelled when the orders to advance from Luxembourg came down.

On January 24th, the 345th Regiment was again on the move, back up into eastern Belgium, near the German border, in small towns east of Limberle. In the evening of the 27th, they received orders to move to St. Vith to relieve the 7th Armored Division which had just taken the city. It took two days of fierce fighting against persistent artillery and small arms fire, but on the 29th, Proctor's F Company, along with I Company of the 3rd Battalion, were the first to advance into St. Vith. The next day the 2nd Battalion moved up and seized Rodgen, east of Schlierbach. F Company took control of Setz for the next 24 hours, after which they fought through waist deep snow to take Schonberg, "moving across country through three feet of snow in the middle of the night [which] made it pretty rough going" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.1). The weather and living conditions in the Ardennes Forest continued to deteriorate all during this time, with reports noting "blinding snowstorms, freezing temperatures, combined with treacherous terrain. Dense woods added to the blackness of normal darkness, reducing visibility to a matter of two or three yards" (87th Division, p. 78).

Nevertheless, Proctor and his F Company continued to push forward towards the German border. Camped in Schonberg and Amelscheid on February 1, they were within 1 kilometer of the border, and the next day the 2nd Battalion crossed over and advanced to Verschneid, where they rested. For these three days, "the men had a good rest and an opportunity to get cleaned up and dried out.... Capt. Ebbers, military government officer for the regiment, gave an orientation on handling German civilians, stressing the idea that our outfit is now on enemy soil and there is to be no fraternization with civilians" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.1). On the 4th came orders for the 2nd Battalion to advance to Auw, at which point they took positions that were within 2000 yards of the massive, legendary, as-yet-intact Siegfried Line.

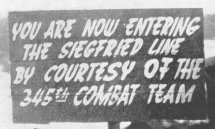

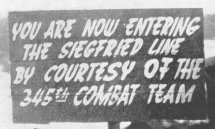

Rheinland (The Siegfried Line). On February 6, 1945 (his wife's 20th birthday), Proctor's F Company broke through the "massive, impregnable" Siegfried Line.

The previous morning, February 5, orders came down for the 345th Regiment to attack the infamous Siegfried Line, which until then had been thought to provide Germany absolute protection from invasion. The zigzag concrete defensive line which snaked its way along the western German border was extremely well fortified; breaking through it "meant knocking out pillboxes covered by six feet of reinforced concrete and four inches of armor plate. It meant getting over roads covered with tellermines and through woods strewn with antipersonnel mines" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p. 2).

The contemporaneous account written by Unit Historian Lt. Gilbert Procter perhaps gives the best flavor of the strategy and fighting: "[The 2nd Battalion's Lt. Colonel decided] to move out that night and take advantage of the hours of darkness for concealment. At 2000 [8:00 p.m.] he moved his battalion out in a column of companies, 'F' Company leading, followed by 'G' Company and then 'E' Company.... By 2300 [11:00 p.m.] 'F' Company had reached Kobscheid and was heading southeast toward their objective.... [They] reached their objective a little before daylight. [The] company commander placed his men in positions to take the first pillbox by surprise. They were successful and before [the enemy] knew what was happening, the first pillbox was in 'F' Company's hands" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.2).

A later Regimental History expanded on F Company's attack this way: "Adverse weather conditions and unfavorable terrain made rapid progress difficult, but Company F ... put forth a vigorous effort to achieve the element of surprise. They confronted the first of the three pillboxes, which dominated an area that included the crossroads and Jagdhs, about 2000 yards southeast of Kobscheid. At dawn they worked to the rear of the pillbox and accepted the surrender of the occupants. The other pillboxes and fifteen bunkers in the area, however, resisted bitterly.... Whenever possible tanks and tank destroyers were moved up to fire directly on the fortification while the troops closed in under the protecting fire. Each pillbox and bunker was mutually supporting, one covering the other making any approach difficult. The pillboxes and bunkers were well camouflaged and invisible until within range of small arms fire, 50-100 yards" (345th Regiment, ca.1946, p.42).

Unit Historian Lt. Procter picks up the story here: "But there were other pillboxes, and [the enemy] was now alert to what was taking place. For four hours, [the commander] fought his company against the pillboxes. The trick seemed to be to get around in the rear of the fortifications where there was a blind spot, and then move in fast with grenades and bazookas. Other methods were to fire at the [pill]boxes from a distance with tank destroyers and tanks, and then move in fast with foot troops. It was rough going, for most of the [pill]boxes were mutually supporting — one covering the other. One had to watch in all directions. Despite heavy artillery barrages and sniper fire from many small wooden bunkers which covered the pillboxes, F Company succeeded in completing its mission. By 1000 [10:00 a.m.] they had knocked out three pillboxes and fifteen wooden bunkers and had taken 100 prisoners" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.3).

Unit Historian Lt. Procter picks up the story here: "But there were other pillboxes, and [the enemy] was now alert to what was taking place. For four hours, [the commander] fought his company against the pillboxes. The trick seemed to be to get around in the rear of the fortifications where there was a blind spot, and then move in fast with grenades and bazookas. Other methods were to fire at the [pill]boxes from a distance with tank destroyers and tanks, and then move in fast with foot troops. It was rough going, for most of the [pill]boxes were mutually supporting — one covering the other. One had to watch in all directions. Despite heavy artillery barrages and sniper fire from many small wooden bunkers which covered the pillboxes, F Company succeeded in completing its mission. By 1000 [10:00 a.m.] they had knocked out three pillboxes and fifteen wooden bunkers and had taken 100 prisoners" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.3).

For its heroism in breaking through the Siegfried Line, members of the 2nd Battalion (Companies E, F, G, & H) were awarded the very rare Presidential Unit Citation — equivalent in rank to the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army's second highest award for "extreme gallantry and risk of life in actual combat with an armed enemy."

Unit Citation

"In the Name of the President of the United States"

for the 2nd Battalion, 345th Infantry Regiment

As authorized by Executive Order 9396 (sec. I, WD Bul. 22, 1943)

The 2nd Battalion, 345th Infantry Regiment, 87th Infantry Division, distinguished itself by its extraordinary heroism, savage aggressiveness and indomitable spirit during its advance through the Siegfried Line and capture of Olzheim, Germany. From 5 through 9 February, 1945, the 2nd Battalion attacked violently and captured Olzheim in the face of extremely difficult terrain, fanatical enemy resistance, and devastating artillery fire. In this exemplary accomplishment, the battalion advanced 11,000 yards, smashing 6,000 yards through the Siegfried Line, neutralized many pillboxes and bunkers, and captured 366 enemy prisoners. The Brilliant tactical planning, rapid capture of assigned objectives and the conspicuous gallantry of each member of the 2nd Battalion, 345th Infantry Regiment, 87th Infantry Division, are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.

(General Orders 246, Headquarters 87th Infantry Division, 19 July 1945, as approved by the Commanding General, United States Army Forces, European Theater (Main).)

|

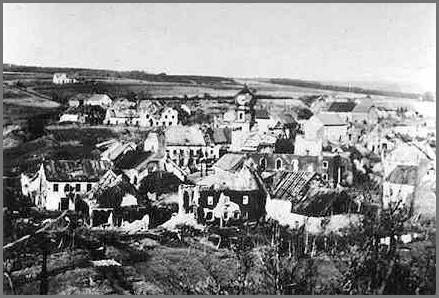

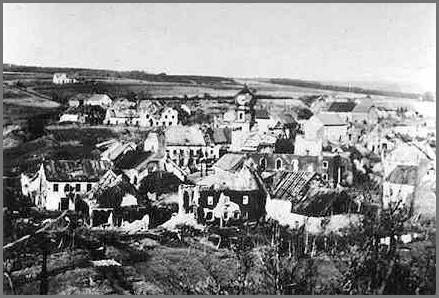

Olzheim. After breaching the Line on February 6, the 2nd Battalion pushed forward and took the town of Jadghs and set up position there, about 2.5 kilometers from their next objective, the town of Olzheim, described as "a small town astride a main German supply route serving Prum" (87th Division, p.82). Sergeant H. M. Trowern, of G Company, remembers an even more important strategic reason for taking the town of Olzheim: It was "the hub of the Siegfried Line communications system. Patton wanted Olzheim because he wanted to take out the communications and break the Siegfried Line up. He wanted the village desperately" (Trowern, 2000, p. 29).

Town of Olzheim, pre-war

By February 8, Proctor's F Company had advanced to within 2000 yards northwest of Olzheim, and the original plans called for them to wait until the 3rd Battalion could come around the town, gain the high ground, and provide cover for F Company to advance. The 3rd Battalion met fierce resistance as they attempted their maneuver, and they were therefore delayed in reaching their destination. Even though the ground leading into Olzheim provided very little cover, exposing F Company to open enemy artillery fire, at 1430 hours (2:30 p.m.) the Regimental Commander ordered them to attack and take the town before dark.

F Company, lacking the protection of the still missing 3rd Battalion, was stopped by sniper fire just 800 yards short of the city, and by 1530 hours (3:30 p.m.) they came under an intense artillery barrage. Proctor's squad leader in the 2nd Platoon in F Company, Staff Sergeant Edward F. Allison, immediately recognized the heavy casualties that were being inflicted by the shelling, and led the squad "against the enemy position which had his company immobilized. He directed the squad in laying heavy fire on the emplacement until he had maneuvered into a position from which he could rush the enemy. [Sgt. Allison] then single handedly charged the position, taking the gun crew prisoners" (345th Regiment, ca.1946, p.50). (Sgt. Allison would later be awarded the Silver Star for his heroism.) With the mortar fire having been eliminated, F Company was able to move into Olzheim, where they instituted a mop-up operation and took 60 prisoners of the remaining German soldiers.

Contemporary accounts from soldiers in the European battlefields tell us much about the mindset of battle -- being caught in the hail of bullets or the thunder of artillery; the sights, smells, and sounds of destruction wrapping around you like a blanket; having to raise your gun, point it at another human being, and quickly fire before he had the time to harm you; watching men you knew and many you didn't fall in action, beyond your reach and beyond your power to rescue; and of course the fear of being shot and dying (or perhaps being shot and not dying) which was never far from any man in those conditions. Scenes from William Fee's powerful diary paint an honest and arresting picture of battle conditions:

When we got most of the way up the hill, a volley of shots and the ripping sound of a German MG burst out some distance ahead and we all hit the ground. The shooting continued, and [the Captain], who'd been up ahead, ran back along the column, crouched over.... Now the Germans began to throw mortar shells at us, so we were told to get out of the open field. Our squad ran into the woods on our right and slowly worked its way up a path that wound around in the woods. When not moving, we lay flat because bullets were zipping around....

Then our squad set up its MGs in the German foxholes. There were not enough holes to go around because some had dead Germans in them who were too heavy for the boys to toss out, so I lay on the ground behind a tree. Shells came crashing down in the woods and some burst in the air above. Shrapnel ripped through the forest, and wood chips flew around. One shell hit the tree I was behind, and branches, pine needles, and clumps of snow fell on us. The smell of burned powder filled the air.... Later we moved further into the woods and remained there a couple of hours. When shelling started, we plopped in the snow. When it stopped, we stood up and tried to dry off.... My new buddy and I did some talking, but mostly praying....

After a moment of rest, [my buddy] said, "Let's go." We crossed the road, and on the other side we moved up beyond a woods. There were tanks there, waiting to attack, and [the colonel] sweating over a map. We went ahead a little and sat in a ditch by the road. Then we realized that the war was right there. Over the hill to our left front came back wounded men from C Company. Some were limping, unassisted; others had a buddy or a medic helping them. Then, down the road to our front, staggered a wounded man, all by himself, a good distance away. Every step he took seemed to be agony and a great effort. After every few, hesitant steps, he fell on his face in the snow. Then he'd struggle painfully to his feet and stagger on. We wanted to run out and help him, but we couldn't, because we knew our platoon would have to move out in a minute. We never found out who he was or what happened to him. (Fee, 1945, p.34,36,15)

|

On that day in Olzheim, only a few days and a few kilometers from where Fee witnessed the above incident, Proctor's fate became the same as that of the lone unknown soldier.

Somewhere near Olzheim, Proctor was wounded in the upper left arm while "on the march." As the surviving records do not say, it is possible he was wounded during the initial advance on the city, or perhaps during Sgt. Allison's heroic efforts to take out the enemy artillery. The various medical records and reports created during the next 2 months disagreed as to when and how his wound was sustained. The first report which has survived (dated March 20) listed the time as 0155 hours (1:55 a.m.) on February 9; later, in a stateside hospital, it was listed as 1530 hours (3:30 p.m.) on February 8 (the exact time his Company was pinned down by sniper and artillery fire). Proctor would later tell his wife that he had taken the point of the march (that is, he was in the lead), and that he was hit as he came up over a ridge.

He fell, and lay in the snow for 9 hours before being found and rescued. He was later told that, had he not fallen in snow, which stanched the bleeding, he would have died long before he was found. [It might be noted here that the discrepancy between the two times given above is 10½ hours, which is almost exactly the length of time said to have elapsed between the time of his wounding and the time of his being rescued. While it is possible that the actual wounding happened at 3:30 p.m. on the 8th and at 1:55 a.m. he was rescued, it is hard to imagine recovery operations like that taking place in the dead of night. Perhaps he was wounded at 1:55 a.m. on the 9th and rescued 9 hours later, approximately 11:00 a.m. However, this means that they would have been "on the march" and under enemy fire in the middle of the night, and this too is improbable.]

Recovery. According to F Company's Morning Report for February 10, 1945, he was shipped on February 9 to the 437th Medical Battalion as a result of being "lightly wounded in action" by a "gunshot wound" to the "left humerus." Reports made the next month in a stateside hospital identified the location as the 101st Evac Hospital in Luxembourg, and the time of his departure from Olzheim as 1930 hours (5:30 p.m.) on the 9th.

One report said the injury was as a result of a rifle bullet, another attributed it to machine gun fire. The report from a Veterans Administration physical examination he was requested to take on July 2, 1946, stated "The arm was wounded by shrapnel" which "passed through the arm, making a wound of entrance on the lower third about 4" long and 1" across.... There is a wound of exit, posterior surface, lower third, of the arm, about 4" long and 1" across."

Part of his recuperation was spent in a couple of English hospitals. On February 14, he arrived at the 154th General Hospital there, where he was treated both for his arm wound and for frostbite on both feet. Records which have survived from the 154th show that on February 22, Proctor was treated for the injury to the left humerus and "peripheral nerve injury," specifically "paralysis [of the] radial nerve." After at least two surgeries and many examinations, on March 20 doctors at the 154th upgraded the classification of the wound to "major," and it was noted that the "radial nerve ... showed no signs of return of function."

In September of 1945, hospital staff summarized his condition this way on a Veterans Administration Application for Compensation for Disability: "Gun shot wound left arm - 2-8-45 - resulted in semi-paralysis of left arm, very slight motion in arm; stiff. Hand numb, unable to close hand completely, no grip. Upper arm badly scarred, bone out of place. Does not have complete motion of shoulder, or wrist. Has practically no use of arm. Also has snow-blindness, first noticed March '45. Effects [sic] eyes when reading for any length of time. Former work was close book work. Also injured rt. knee in fall, no treatment, was on the march."

On April 20, he was transferred to the 117th General Hospital, which was the date he was shipped back to the States. He crossed the Atlantic on the S.S. Uruguay, on which he was confined to Bed 4 in Ward 119. On arrival in the States on April 30, he was taken to McGuire General Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, where he was admitted on May 9. It was from McGuire that he was discharged from the Army on November 19, 1945.

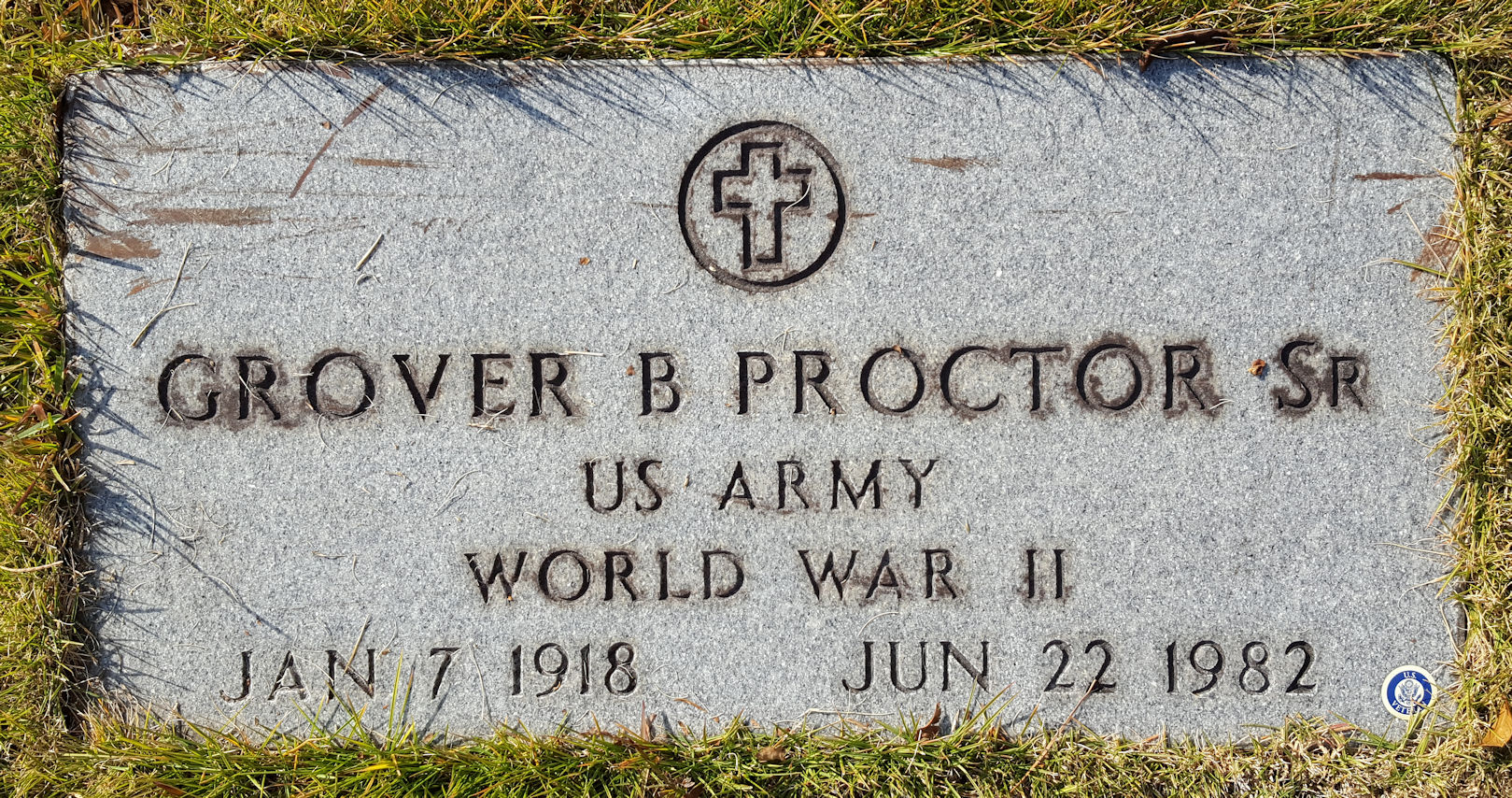

Decorations and Discharge. According to the Chief of the Army Medals Section at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, the decorations and citations Proctor was awarded include the following:

- Presidential Unit Citation

(awarded to members of the 2nd Battalion who breached the Siegfried Line)

- The Bronze Star Medal, for "Heroic or Meritorious Achievement"

- The Purple Heart "for Military Merit"

- Combat Infantryman Badge

- EAME Campaign Ribbon with two (2) Bronze Service Stars

- Good Conduct Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- WW II Victory Medal

- Sharpshooter Badge with Rifle Bar

- Honorable Service Lapel Button WWII

His "Continental Service" (U.S.) was given as 1 year, 2 months, and 28 days; his "Foreign Service" was 4 months and 19 days. The reason given for his separation was "AR 615-361 Certificate of Disability for Discharge." His total mustering out pay was $300, and he was issued one lapel button on his discharge.

Some Personal Notes from His Son:

Some Personal Notes from His Son:

My father finished his time in the military at the rank of Pfc (Private first class), but family stories say that he was in line to move up, jumping past corporal, to buck sergeant when he was wounded. It's why he was "in the point," leading the troop movement. (Because of when he was drafted, he was about 6 to 8 years older than almost all of his fellow Pfc's, who were mere boys of 18 and 19 years old. So I suppose it was natural that he would move into a leadership role, once he had fought side by side with them, his status as a "replacement" had been overcome, and he had been accepted into the fellowship of his platoon.)

Even though the breaching of the Siegfried Line is remarkable enough in and of itself to warrant Hollywood's attention, I know of no movie nor any thorough treatment in books that chronicles F Company's and the 2nd Battalion's efforts inside the German border. (That latter fact has been both scholarly and personally frustrating to me!) But I have talked with many men who served in my father's Company, and they are incredibly wonderful, personable, articulate, deeply feeling, and quietly heroic men -- all of whom have told me they are touched by my research and what I have written. They (rightly) look on this as also a tribute to them, and I think many of them wish their sons and daughters would take a similar interest.

One of the men in his Company once took me so off guard on the telephone that tears fiercely welled in my eyes, and my voice shook when I tried to reply. He said it simply, but with great conviction; it was of great urgency to him for me to hear it. He said, "I want you to know your father was a hero!"

Much has been made recently (at long last) about the extraordinary accomplishments of this "greatest generation," and how they did nothing less than preserve liberty for the entire world. In fact, this uncommon valor of which we speak truly flowed from everyday men and women, cast into unimaginable situations, called on to do the impossible and to conquer the insurmountable -- which, selflessly, they did simply because they knew that it all depended on them and that it must be done.

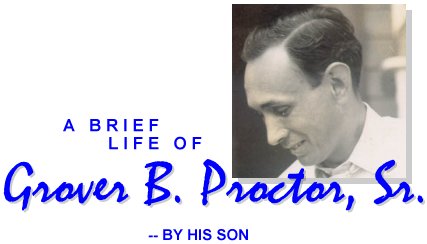

My father was a complex man, and it would be hard to summarize him in a few paragraphs. But anyone drawn to read this page should be rewarded, in the end, by being allowed to know him more fully. To give a small sense of who he was, here is a quote from the dedication page of my doctoral dissertation. It's just a few words, but I tried to capture him as accurately as I could:

Grover B. Proctor, Sr.

my father,

whose diligence, selflessness, quiet strength, and gentleness of spirit

set an example that continues to inspire and lead me.

He was and is my hero.

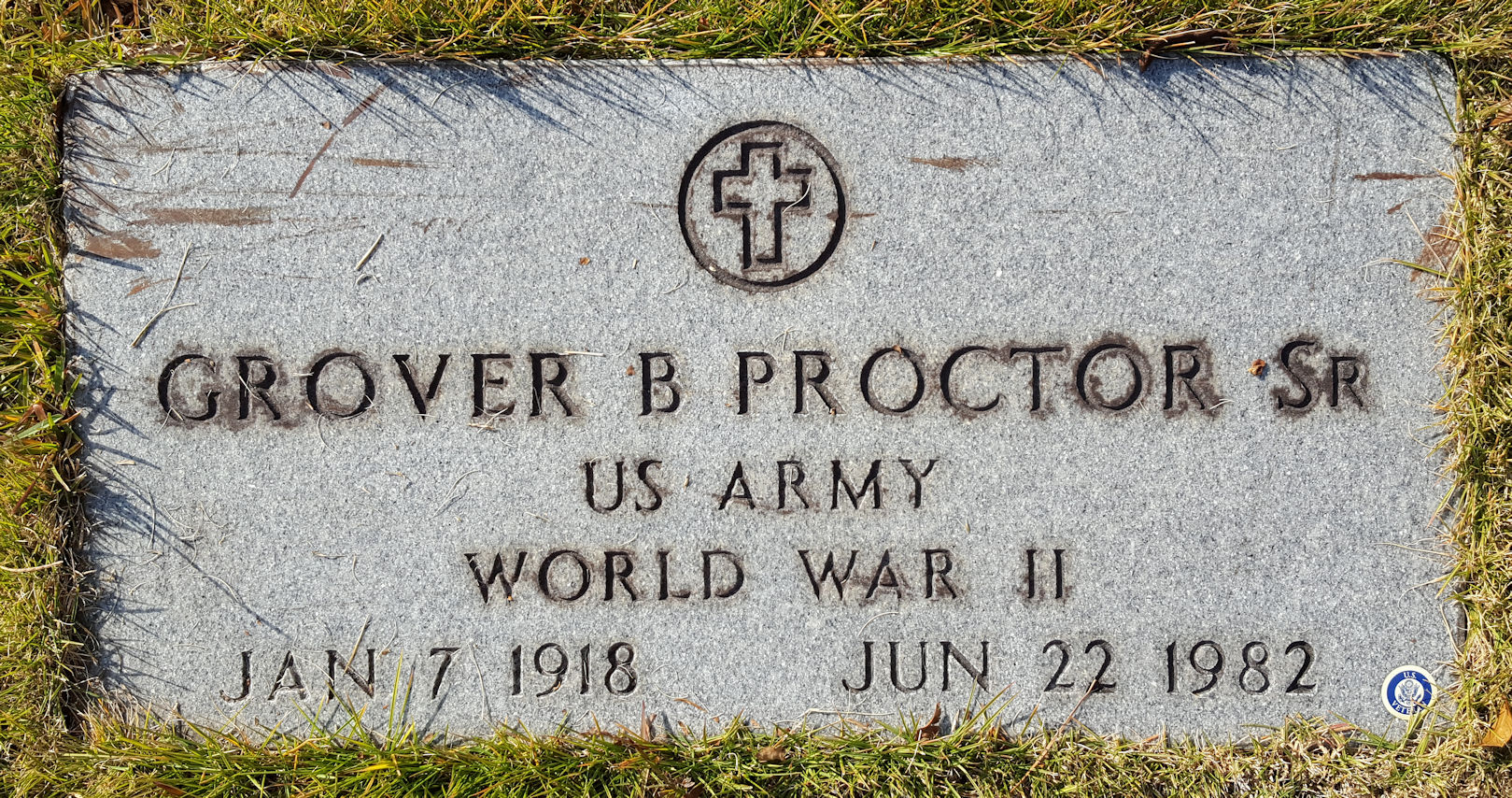

Grover B. Proctor, Sr. died on June 22, 1982 in Raleigh, N.C.

Proudly displayed on the banner from the side of the ship going home was the news that the 345th Regiment of the Golden Acorn (87th) Division had breached the Siegfried Line.

|

|

References:

345th Regiment, U.S. Army. (ca.1946). "Historical Data and Background of the 345th Infantry Regiment: From 10 November 1942 to 21 September 1945". Official U.S. Army History, now stored in Washington, DC at the U.S. National Archives.

87th Infantry Division, U.S. Army. (ca.1946). "The 345th Infantry Regiment" in "An Historical and Pictorial Record of the 87th Infantry Division in World War II: 1942-1945".

Bain, J. (1999, May 30). Personal correspondence.

Fee, W.W. (1945). "With the Eleventh Armored Division in the Battle of the Bulge: A Retrospective Diary". Silver Spring, MD: self-published.

Prather, W.T. (1999, June 11). Personal correspondence.

Procter, G. (1945, January 11). "History of 345th Infantry Regiment, 1 December 1944 thru 31 December 1944". U.S. Army: Declassified 4 December 1946, Authority NND735017, now stored in Washington, DC at the U.S. National Archives.

Procter, G. (1945, February 6). "History of 345th Infantry Regiment, 1 January 1945 thru 31 January 1945". U.S. Army: Declassified 4 December 1946, Authority NND735017, now stored in Washington, DC at the U.S. National Archives.

Procter, G. (1945, March 8). "History of 345th Infantry Regiment, 1 February 1945 thru 28 February 1945". U.S. Army: Declassified 4 December 1946, Authority NND735017, now stored in Washington, DC at the U.S. National Archives.

Strang, B. (1999, June 11). Personal correspondence.

Trowern, H.M. (2000, March). Battle of the Bulge oral history. The Golden Acorn News, 42(1), 24-31.

Williams, M. (1958). United States in World War II: Special Studies: Chronology 1941-1945. Washington, DC: U.S. Army.

CREDIT:

Photo restoration and colorization of two pictures of Pfc. Grover Proctor (first and second paragraphs, right) was done by Melanie Bevill Arrowood, Asheville, North Carolina. Thank you, Melanie!

|

Some Personal Notes from His Son:

Some Personal Notes from His Son:

Grover Belmont Proctor was born on January 7, 1918 in Upper Town Creek Township (near Rocky Mount) in Edgecombe County, North Carolina. He married Edna Ruth Hooks of Apex, N.C., on July 11, 1943, and, at the time of his entry into the Army, he gave as his address P.O. Box 111, Apex, N.C. He was an employee of the railroad, and the Army listed his civilian occupation and reference number as "Clerk, General (1-05-010)" with the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. The report from his Army induction physical examination gives some description of him at this time. He is listed as a "white, married, U.S. citizen," with one dependent, 5'5" tall, 115 pounds, with gray eyes and black hair. It lists his complexion as "ruddy," his eyesight as 20/20 in both eyes, and he is described as having a "light frame" and "fair posture."

Grover Belmont Proctor was born on January 7, 1918 in Upper Town Creek Township (near Rocky Mount) in Edgecombe County, North Carolina. He married Edna Ruth Hooks of Apex, N.C., on July 11, 1943, and, at the time of his entry into the Army, he gave as his address P.O. Box 111, Apex, N.C. He was an employee of the railroad, and the Army listed his civilian occupation and reference number as "Clerk, General (1-05-010)" with the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. The report from his Army induction physical examination gives some description of him at this time. He is listed as a "white, married, U.S. citizen," with one dependent, 5'5" tall, 115 pounds, with gray eyes and black hair. It lists his complexion as "ruddy," his eyesight as 20/20 in both eyes, and he is described as having a "light frame" and "fair posture."

Unit Historian Lt. Procter picks up the story here: "But there were other pillboxes, and [the enemy] was now alert to what was taking place. For four hours, [the commander] fought his company against the pillboxes. The trick seemed to be to get around in the rear of the fortifications where there was a blind spot, and then move in fast with grenades and bazookas. Other methods were to fire at the [pill]boxes from a distance with tank destroyers and tanks, and then move in fast with foot troops. It was rough going, for most of the [pill]boxes were mutually supporting — one covering the other. One had to watch in all directions. Despite heavy artillery barrages and sniper fire from many small wooden bunkers which covered the pillboxes, F Company succeeded in completing its mission. By 1000 [10:00 a.m.] they had knocked out three pillboxes and fifteen wooden bunkers and had taken 100 prisoners" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.3).

Unit Historian Lt. Procter picks up the story here: "But there were other pillboxes, and [the enemy] was now alert to what was taking place. For four hours, [the commander] fought his company against the pillboxes. The trick seemed to be to get around in the rear of the fortifications where there was a blind spot, and then move in fast with grenades and bazookas. Other methods were to fire at the [pill]boxes from a distance with tank destroyers and tanks, and then move in fast with foot troops. It was rough going, for most of the [pill]boxes were mutually supporting — one covering the other. One had to watch in all directions. Despite heavy artillery barrages and sniper fire from many small wooden bunkers which covered the pillboxes, F Company succeeded in completing its mission. By 1000 [10:00 a.m.] they had knocked out three pillboxes and fifteen wooden bunkers and had taken 100 prisoners" (Procter, 8 March 1945, p.3).